Having completed my series on Britain’s Overseas Territories I was struck by how, even in the ‘post-colonial’ modern world, colonialism is still an important feature of international relations. Critically modern day colonialism also exists, not only as a legacy of the British Empire and as a British phenomenon, but as part of the politics of many modern day states, both in Europe and beyond.

Territories round the world that can be considered 21st century colonies:

|

Britain |

France |

Netherlands |

|

Akrotiri & Dhekelia |

French Guiana |

Aruba |

|

Anguilla |

Guadeloupe |

Curacao |

|

Bermuda |

Martinique |

Sint Maarten |

|

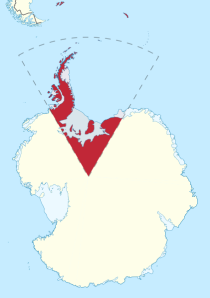

British Antarctic Territory |

Reunion |

Caribbean Netherlands (Bonaire, Sint Eustatius & Saba) |

|

Mayotte |

||

|

British Indian Ocean Territory |

French Polynesia |

|

|

St Barthelemy |

||

|

British Virgin Islands |

St Martin |

Spain |

|

Cayman Islands |

St Pierre & Miquelon |

Cueta |

|

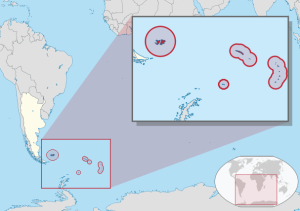

Falkland Islands |

Wallis & Fortuna |

Melilla |

|

Gibraltar |

New Caledonia |

|

|

Montserrat |

USA |

|

|

Pitcairn Islands |

Denmark |

US Virgin Islands |

|

St Helena, Ascension & Tristan da Cunha |

Greenland |

Guam |

|

Faroe Islands |

Puerto Rico |

|

|

South Georgia & South Sandwich Islands |

American Samoa |

|

|

Northern Mariana Islands |

||

|

Turks & Caicos Islands |

But should colonialism, even its modern form (which is not seen as imperialist) continue to exists? Is it a harmless political structure, a political benefit to these overseas territories or a repressive system of international governance?

Within modern political discourse the greatest argument is for an end to colonialism and there are many calls for these overseas territories to become independent states. They want to end the dominance of European and American powers over the political structures of land that often is geographical far away from central political authority.

The roots of the argument against colonialism stem from a belief that states deserve national sovereignty, i.e. the ability to determine their own affairs and dictate their own political futures. This sovereignty may be determined along ethnic, religious or cultural lines or may derive from a shared history within a certain community, but what is constant is that the people of the nation must be allowed to control the political, economic and social affairs of the nation state they belong to.

The desire for national sovereignty has been a very common factor in the development of the modern political system, with nations across the world supporting nationalist, anti-colonial regimes in the pursuit of independence. Solely within the history of the British Empire, many famous 20th century individuals, praised the world over, dedicated their lives to fighting colonialism . These included Gandhi (who helped achieve India’s independence from Britain) and General Nasser (the first leader of an independent Egypt). These figures have achieved global political status and this is largely because of the desire to achieve a colonial free society. It has become a common tradition to criticise Western colonialism and the interpretations of the world system that colonialism has created.

Writers, such as Edward Said, in his book Orientalism, were quick to argue that the way the world system is understood is a legacy of colonialism and that this has twisted our understanding of global politics. This understanding failed to recognise the interests and traditions of local cultures and as a result created a colonial and even post-colonial system where, as Edward Said argues, the West has created an image of the Middle East, Asia and Africa as something ‘other’, something mystical, but often uncivilised. Thus politics has been skewed by this image and it has greatly affected political interactions in the modern world.

The opposition to colonialism is a well funded argument as, for most nations who experienced colonialism, their experience of political domination was not a positive one. Many were subjugated to oppressive political structures that contained inherent elements of racism and segregation. Some, such as the Belgian Congo, were even famed for the stories of great violence at the hands of the colonial masters. Others simply rejected the notion that a foreign power could dictate the political affairs of their nation state.

This anti-imperialist, anti-colonial rhetoric has not ended with the end of the Age of Empire. Within many of the territories still controlled by a colonial power there is a section of the community calling for independence, seeking separation from the Western nations who control them. In territories, such as Bermuda, there have been reviews of the political status of this island territory, with some politicians and officials calling for independence and separation from the UK.

However within other territories the rhetoric doesn’t focus on independence but rather ‘repatriation’. In the Falkland Islands much of the international political discussion in focused on whether or not to ‘return’ the territory back to Argentina and it is the same in Gibraltar, where the focus is on whether or not the territory should return to be part of Spain. Spain and Argentina both maintain that by removing Britain as the colonial power in the respective territories they are readdressing the balance of political affairs in the region; returning territory they see as historically theirs.

However for some looking at the situation they do not see repatriation as freedom from colonialism. These territories have developed a separate identity, a separate culture, even a separate language and therefore any repatriation would likely involve the imposition of a new political or cultural tradition on the territory. Rupert Emerson, in his article Colonialism, argues that a condition of colonialism is that there “should be a significant disparity in power between those who govern and those on whom alien rule is imposed” (Emerson, R., Colonialism, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1969, 4). With a distinct culture and identity and a history that is so disparate from the new power, territories are clearly going to be at a power disadvantage once they are assimilated into the wider country.

With questions on both sides of the debate it is key to ask whether any change to the political situation should occur. The debate for removing colonialism is well established in modern political discourse but yet after over 100 years of decolonialisation we still have colonies.

One of the motivations for the maintenance of colonies is that colonialism, in the modern world, acts as a benefit for these territories. Their special economic status, access to self-determination with regional politics and links, no matter how distant, to leading world nations has all proved to be a benefit to the colonies. Within the Caribbean some of the territories, such as Puerto Rico, have benefited politically from its involvement and connections to the USA, whilst others, including Bermuda, Sint Maarten and Saint Martin (both territories share the same island) and the Cayman Islands, have some of the highest standards of living in the world.

Whilst these are territories that have benefited from their status as colonies, others in the modern world are dependent on the home country (metropolis) for financial aid and help maintaining their economies. St Helena and the Pitcairn Islands, both British territories, are examples of colonies that rely nearly entirely on this ‘metropolis’. They both rely on British foreign developmental aid to function economically and if they were to become independent the security, both political and economic, offered by the colonial power, would go.

Ultimately arguments over whether colonialism in the 21st century is right or wrong are meaningless without context. When nation states debate the political status of territories, such as Gibraltar or the Falkland Islands they quote theoretical and ideological views on colonialism. They quote history, to highlight the excesses of colonialism in the past but fundamentally fail to listen to the desires of the people living in these territories.

If a nation dislikes the rule of a foreign power and decided to push for independence then we can argue that colonialism, in that context, is wrong. This is certainly the position of the British government, who have stated repeatedly that they will respect the wishes of the populations of their overseas territories. They have offered populations, such as that in the Falklands, the opportunity to express their views on national sovereignty and whether they desire it. If the answer received is that they want to change their political status, Britain has pledged to listen and support this.

However ‘repatriation’ to another nation is not the end to colonialism, as it is often portrayed as in the world media. By assimiliating a territory that has a separate political and cultural identity into a wider national framework it is simply establishing the end of geographic colonialism and the start of social colonialism as a new political system, culture etc is imposed on this newly integrated part of society. Repatriation can only work if the territory shares the same culture of the new nation, and the same desire to be united.

But with colonialism existing even into the 21st century it is clear that these territories do not necessarily seek decolonialisation and instead are proud to remain a part of the colonial power. If that is the wish of the people, to remain a colony, then this was be supported as ardently as call for an end to colonialism are. It must be accepted that although national sovereignty is important, individual and community sovereignty is also important and through this colonialism may exist well into the 21st century.

By Peter Banham

See Also: